고유가는 세계경제 성장을 둔화시킬 수 있고, 계속해서 대체 연료로의 전환을 가속화시킬 것으로 보인다고 앨런 그린스펀(Alan Greenspan) 美 연준 의장이 18일 일본에서 가진 연설을 통해 지적했다.그린스펀 의장은 이날 도쿄에서 일본상공회의소 및 게이단렌(經團聯) 초청 강연에서 "비록 세계경제의 확장 국면이 올해 여름을 거치면서 상당히 강화된 것으로 보이지만, 최근 에너지물가의 급등은 명백히 경제성장을 둔화시킬 것으로 예상된다"고 경고했다.그러나 그는 또한 세계경제가 30년 전에 비해 일인당 석유사용 규모가 2/3로 줄어든 것 때문에, "현재와 같은 고유가 사태의 영향은 비록 무시할 수 없을 정도이긴 하지만 경제성장 및 인플레이션에 미치는 결과는 1970년대에 비해서는 상당히 낮은 수준일 것"이라고 낙관적인 전망을 덧붙였다.연준은 올해 초 배럴당 44달러하던 국제유가가 20달러나 급등한 사실에 대해 계속 우려를 표명하고 있는 중이다. 고유가는 성장을 둔화시키는 동시에 인플레이션 압력을 상승시키는 요인이다.최근 연준은 이러한 요인 중에서 인플레 쪽에 비중을 두면서 금리인상 추세를 지속할 것이란 입장을 선명하게 드러냈다.그린스펀은 지난 1985년 유가 급락사태를 지적하며 미국의 GDP 1달러 중 에너지 소비를 나타내는 에너지 원단위(energy intensity)가 낮아진 점에 대해 지적했다. 이처럼 유가가 상승할 수록 "에너지 원단위의 좀 더 급격한 하락세가 거의 불가피해 보인다"고 그는 말했다.특히 그린스펀은 최근 미국의 휘발유 소비가 현저하게 줄어든 사실을 지적하면서, 이 같은 원단위 하락세가 진행형임을 강조했다.또한 소비의 감소가 경제활동의 위축보다는 소비자들의 보수적인 태도로 인한 것이라면 연준은 소비자들이 고유가를 제대로 극복하고 있다고 보고 좀 더 편안하게 금리를 올릴 수 있을 것으로 예상된다.그린스펀 의장은 장기적인 안목에서는 "역사가 하나의 지침이 된다면 석유는 매장석유가 고갈되기 전에 결국 좀 더 비용이 낮은 대체연료로 대체될 것"이라며, "21세기 중반 이전에 이 같은 주력 에너지원의 대체과정이 개시될 것으로 본다"고 말했다.그는 아직도 석탄 매장량이 풍부한데도 석유가 이를 대체한 것은, 나무가 많아도 석탄이 이를 대체한 것처럼 그 에너지 효율성과 낮은 비용 때문이라고 설명했다.하지만 그린스펀 의장은 이러한 새로운 에너지원으로의 이행 과정은 장기간이 소요될 뿐 아니라 중국과 같은 높은 에너지 원단위를 가진 경제의 출현으로 인해 그 속도가 더 느려질 수 있다고 경고했다.이런 점에서 "세계경제는 당분간 석유시장에 대한 지정학적인 그리고 또다른 불확실성 속에 살아가야 할 것"으로 보인다고 그는 지적했다.Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan: EnergyBefore the Japan Business Federation, the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Japan Association of Corporate Executives, Tokyo, JapanOctober 17, 2005 Even before the devastating hurricanes of August and September 2005, world oil markets had been subject to a degree of strain not experienced for a generation. Increased demand and lagging additions to productive capacity had eliminated a significant amount of the slack in world oil markets that had been essential in containing crude oil and product prices between 1985 and 2000. In such tight markets, the shutdown of oil platforms and refineries last month by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita was an accident waiting to happen. In their aftermath, prices of crude oil worldwide moved sharply higher, and with refineries stressed by a shortage of capacity, margins for refined products in the United States roughly doubled. Prices of natural gas soared as well. Oil prices had been persistently edging higher since 2002 as increases in global oil consumption progressively absorbed the buffer of several million barrels a day in excess capacity that stood between production and demand. Any pickup in consumption or shortfall in production for a commodity as price inelastic in the short run as oil was bound to be immediately reflected in a spike in prices. Such a price spike effectively represented a tax that drained purchasing power from oil consumers. Although the global economic expansion appears to have been on a reasonably firm path through the summer months, the recent surge in energy prices will undoubtedly be a drag from now on. In the United States, Japan, and elsewhere, the effect on growth would have been greater had oil not declined in importance as an input to world economic activity since the 1970s. How did we arrive at a state in which the balance of world energy supply and demand could be so fragile that weather, not to mention individual acts of sabotage or local insurrection, could have a significant impact on economic growth? Even so large a weather event as August and September's hurricanes, had they occurred in earlier decades of ample oil capacity, would have had hardly noticeable effects on crude prices if producers placed their excess supplies on the market or on product prices if idle refinery capacity were activated. The history of the world petroleum industry is one of a rapidly growing industry seeking the stable prices that have been seen by producers as essential to the expansion of the market. In the early twentieth century, pricing power was firmly in the hands of Americans, predominately John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil. Reportedly appalled by the volatility of crude oil prices that stunted the growth of oil markets in the early years of the petroleum industry, Rockefeller had endeavored with some success to stabilize those prices by gaining control by the turn of the century of nine-tenths of U.S. refining capacity. But even after the breakup of the Standard Oil monopoly in 1911, pricing power remained with the United States--first with the U.S. oil companies and later with the Texas Railroad Commission, which raised limits on output to suppress price spikes and cut output to prevent sharp price declines. Indeed, as late as 1952, crude oil production in the United States (44 percent of which was in Texas) still accounted for more than half of the world total. Excess Texas crude oil capacity was notably brought to bear to contain the impact on oil prices of the nationalization of Iranian oil a half-century ago. Again, excess American oil was released to the market to counter the price pressures induced by the Suez crisis of 1956 and the Arab-Israeli War of 1967. Of course, concentrated control in the hands of a few producers over any resource can pose potential problems. In the event, that historical role ended in 1971, when excess crude oil capacity in the United States was finally absorbed by rising world demand. At that point, the marginal pricing of oil, which for so long had been under the control of international oil companies, predominantly American, abruptly shifted to a few large Middle East producers and to greater market forces than those that they and the other members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) could contain. To capitalize on their newly acquired pricing power, many producing nations, especially in the Middle East, nationalized their oil companies. But the full magnitude of the pricing power of the nationalized oil companies became evident only in the aftermath of the oil embargo of 1973. During that period, posted crude oil prices at Ras Tanura, Saudi Arabia, rose to more than $11 per barrel, a level significantly above the $1.80 per barrel that had been unchanged from 1961 to 1970. The further surge in oil prices that accompanied the Iranian Revolution in 1979 eventually drove up prices to $39 per barrel by February 1981 ($75 per barrel in today's prices). The higher prices of the 1970s abruptly ended the extraordinary growth of U.S. and world consumption of oil and the increased intensity of its use that was so evident in the decades immediately following World War II. Since the more than tenfold increase in crude oil prices between 1972 and 1981, world oil consumption per real dollar equivalent of global gross domestic produce (GDP) has declined by approximately one-third. In the United States, between 1945 and 1973, consumption of petroleum products rose at a startling average annual rate of 4-1/2 percent, well in excess of growth of our real GDP. However, between 1973 and 2004, oil consumption grew in the United States, on average, at only 1/2 percent per year, far short of the rise in real GDP. In consequence, the ratio of U.S. oil consumption to GDP fell by half. Much of the decline in the ratio of oil use to real GDP in the United States has resulted from growth in the proportion of GDP composed of services, high-tech goods, and other presumably less oil-intensive industries. Additionally, part of the decline in this ratio is due to improved energy conservation for a given set of economic activities, including greater home insulation, better gasoline mileage, more efficient machinery, and streamlined production processes. These trends have been ongoing but have likely intensified of late with the sharp, recent increases in oil prices. In Japan, which until recently was the world's second largest oil consumer, the growth of demand was also strong before the developments of the 1970s. Subsequently, shocked by the increase in prices and without indigenous production to cushion the effects on incomes, Japan sharply curtailed the growth of its oil use, reducing the ratio of oil consumption to GDP by about half as well. Although the production quotas of OPEC have been a significant factor in price determination for a third of a century, the story since 1973 has been as much about the power of markets as it has been about power over markets. The incentives to alter oil consumption provided by market prices eventually resolved even the most seemingly insurmountable difficulties posed by inadequate supply outside the OPEC cartel. Many observers feared that the gap projected between supply and demand in the immediate post-1973 period would be so large that rationing would be the only practical solution. But the resolution did not occur that way. In the United States, to be sure, mandated fuel-efficiency standards for cars and light trucks induced the slower growth of gasoline demand. Some observers argue, however, that, even without government-enforced standards, market forces would have led to increased fuel efficiency. Indeed, the number of small, fuel-efficient Japanese cars that were imported into U.S. markets rose throughout the 1970s as the price of oil moved higher. Moreover, at that time, prices were expected to go still higher. For example, the U.S. Department of Energy in 1979 had projections showing real oil prices reaching nearly $60 per barrel by 1995--the equivalent of more than $120 in today's prices. The failure of oil prices to rise as projected in the late 1970s is a testament to the power of markets and the technologies they foster. Today, the average price of crude oil, despite its recent surge, is still in real terms below the price peak of February 1981. Moreover, since oil use, as I noted, is only two-thirds as important an input into world GDP as it was three decades ago, the effect of the current surge in oil prices, though noticeable, is likely to prove significantly less consequential to economic growth and inflation than the surge in the 1970s. The petroleum industry's early years of hit-or-miss exploration and development of oil and gas has given way to a more systematic, high-tech approach. The dramatic changes in technology in recent years have made existing oil and natural gas reserves stretch further while keeping energy costs lower than they otherwise would have been. Seismic imaging and advanced drilling techniques are facilitating the discovery of promising new reservoirs and are enabling the continued development of mature fields. Accordingly, one might expect that the cost of developing new fields and, hence, the long-term price of new oil and gas would have declined. And, indeed, these costs have declined, though less than they might otherwise have done. Much of the innovation in oil development outside OPEC, for example, has been directed at overcoming an increasingly inhospitable and costly exploratory environment, the consequence of more than a century of draining the more immediately accessible sources of crude oil. Still, consistent with declining long-term marginal costs of extraction, distant futures prices for crude oil moved lower, on net, during the 1990s. The most-distant futures prices fell from a bit more than $20 per barrel before the first Gulf War to less than $18 a barrel on average in 1999. Such long-term price stability has eroded noticeably over the past five years. Between 1991 and 2000, although spot prices ranged between $11 and $35 per barrel, distant futures exhibited little variation. Since then, distant futures prices have risen sharply. In early August, prices for delivery in 2011 of light sweet crude breached $60 per barrel, in line with recent increases in spot prices. This surge arguably reflects the growing presumption that increases in crude oil capacity outside OPEC will no longer be adequate to serve rising world demand going forward, especially from emerging Asia. Additionally, the longer-term crude price has presumably been driven up by renewed fears of supply disruptions in the Middle East and elsewhere. But the opportunities for profitable exploration and development in the industrial economies are dwindling, and the international oil companies are currently largely prohibited, restricted, or face considerable political risk in investing in OPEC and other developing countries. In such a highly profitable market environment for oil producers, one would have expected a far greater surge of oil investments. Indeed, some producers have significantly ratcheted up their investment plans. But because of the geographic concentration of proved reserves, much of the investment in crude oil productive capacity required to meet demand, without prices rising unduly, will need to be undertaken by national oil companies in OPEC and other developing economies. Although investment is rising, the significant proportion of oil revenues invested in financial assets suggests that many governments perceive that the benefits of investing in additional capacity to meet rising world oil demand are limited. Moreover, much oil revenue has been diverted to meet the perceived high-priority needs of rapidly growing populations. Unless those policies, political institutions, and attitudes change, it is difficult to envision adequate reinvestment into the oil facilities of these economies. Besides feared shortfalls in crude oil capacity, the status of world refining capacity has become worrisome as well. Crude oil production has been rising faster than refining capacity over the past decade. A continuation of this trend would soon make lack of refining capacity the binding constraint on growth in oil use. This may already be happening in certain grades, given the growing mismatch between the heavier and more sour content of world crude oil production and the rising world demand for lighter, sweeter petroleum products. There is thus an especial need to add adequate coking and desulphurization capacity to convert the average gravity and sulphur content of much of the world's crude oil to the lighter and sweeter needs of product markets, which are increasingly dominated by transportation fuels that must meet ever more stringent environmental requirements. Yet the expansion and the modernization of world refineries are lagging. For example, no new refinery has been built in the United States since 1976. The consequence of lagging modernization is reflected in a significant widening of the price spread between the higher priced light sweet crudes such as Brent and the heavier crudes such as Maya. To be sure, refining capacity continues to expand, albeit gradually, and exploration and development activities are ongoing, even in developed industrial countries. Conversion of the vast Athabasca oil sands reserves in Alberta to productive capacity, while slow, has made this unconventional source of oil highly competitive at current market prices. However, despite improved technology and high prices, proved reserves in the developed countries are being depleted because additions to these reserves have not kept pace with production. * * *The production, demand, and price outlook for oil beyond the current market turbulence will doubtless continue to reflect longer-term concerns. Much will depend on the response of demand to price over the longer run. If history is any guide, should higher prices persist, energy use over time will continue to decline relative to GDP. In the wake of sharply higher prices, the oil intensity of the U.S. economy, as I pointed out earlier, has been reduced by about half since the early 1970s. Much of that displacement was achieved by 1985. Progress in reducing oil intensity has continued since then, but at a lessened pace. For example, after the initial surge in the fuel efficiencies of our light motor vehicles during the 1980s, reflecting the earlier run-up in oil prices, improvements have since slowed to a trickle. The more-modest rate of decline in the energy intensity of the U.S. economy after 1985 should not be surprising, given the generally lower level of real oil prices that have prevailed since then. With real energy prices again on the rise, more-rapid decreases in the intensity of energy use in the years ahead seem virtually inevitable. Long-term demand elasticities over the past three decades have proved noticeably higher than those evident in the short term. Indeed, gasoline consumption has declined markedly in the United States in recent weeks, presumably partly as a consequence of higher prices. * * *Altering the magnitude and manner of energy consumption will significantly affect the path of the global economy over the long term. For years, long-term prospects for oil and natural gas prices appeared benign. When choosing capital projects, businesses in the past could mostly look through short-run fluctuations in oil and natural gas prices, with an anticipation that moderate prices would prevail over the longer haul. The recent shift in expectations, however, has been substantial enough and persistent enough to direct business-investment decisions in favor of energy-cost reduction. Over the past decade, energy consumed, measured in British thermal units, per real dollar of gross nonfinancial, non-energy corporate product in the United States has declined substantially, and this trend may be expected to accelerate in coming years. In Japan, as well, energy use has declined as a fraction of GDP, but these savings were largely achieved in previous decades, and energy intensity has been flat more recently. We can expect similar increases in oil efficiency in the rapidly growing economies of East Asia as they respond to the same set of market incentives. But at present, China consumes roughly twice as much oil per dollar of GDP as the United States, and if, as projected, its share of world GDP continues to increase, the average improvements in world oil-intensity will be less pronounced than the improvements in individual countries, viewed separately, would suggest. * * *We cannot judge with certainty how technological possibilities will play out in the future, but we can say with some assurance that developments in energy markets will remain central in determining the longer-run health of our nations' economies. The experience of the past fifty years--and indeed much longer than that--affirms that market forces play a key role in conserving scarce energy resources, directing those resources to their most highly valued uses. However, the availability of adequate productive capacity will also be driven by nonmarket influences and by other policy considerations. To be sure, energy issues present policymakers with difficult tradeoffs to consider. The concentration of oil reserves in politically volatile areas of the world is an ongoing concern. But that concern and others, one hopes, will be addressed in a manner that, to the greatest extent possible, does not distort or stifle the meaningful functioning of our markets. Barring political impediments to the operation of markets, the same price signals that are so critical for balancing energy supply and demand in the short run also signal profit opportunities for long-term supply expansion. Moreover, they stimulate the research and development that will unlock new approaches to energy production and use that we can now only barely envision. Improving technology and ongoing shifts in the structure of economic activity are reducing the energy intensity of industrial countries, and presumably recent oil price increases will accelerate the pace of displacement of energy-intensive production facilities. If history is any guide, oil will eventually be overtaken by less-costly alternatives well before conventional oil reserves run out. Indeed, oil displaced coal despite still vast untapped reserves of coal, and coal displaced wood without denuding our forest lands. New technologies to more fully exploit existing conventional oil reserves will emerge in the years ahead. Moreover, innovation is already altering the power source of motor vehicles, and much research is directed at reducing gasoline requirements. We will begin the transition to the next major sources of energy, perhaps before midcentury, as production from conventional oil reservoirs, according to central-tendency scenarios of the U.S. Department of Energy, is projected to peak. In fact, the development and application of new sources of energy, especially nonconventional sources of oil, is already in train. Nonetheless, the transition will take time. We, and the rest of the world, doubtless will have to live with the geopolitical and other uncertainties of the oil markets for some time to come. [뉴스핌 Newspim] 김사헌 기자 herra79@newspim.com

[관련키워드]

[뉴스핌 베스트 기사]

사진

사진

[단독] "반차 쓰면 30분 일찍 퇴근"

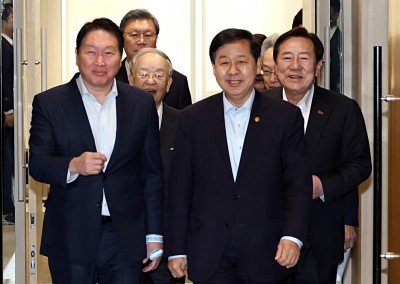

[세종=뉴스핌] 양가희 기자 = 반차를 사용해 하루 4시간 근무할 경우 휴게시간을 사용하지 않고 퇴근할 수 있도록 보장하는 내용의 근로기준법 개정안이 국회에서 발의된다. 근로시간 단축, 연차 휴가 분할 사용, 육아·돌봄 등으로 반일 근무 형태가 확대된 가운데 현행 법체계는 4시간 근무한 근로자에게 법정 휴게시간 30분을 부여하고 있다. 개정안은 휴게시간 때문에 퇴근이 늦어지는 불편을 해소한다는 취지에서 마련됐다.

12일 국회에 따르면 박홍배 더불어민주당 의원은 이 같은 내용을 담은 근로기준법 개정안을 이르면 이번 주 대표 발의할 예정이다.

현행 근로기준법은 4시간 근로한 경우 30분 이상, 8시간 근로한 경우 1시간 이상의 휴게시간을 부여한다. 휴식은 근로시간 도중에 부여하도록 규정됐다. 통상 8시간 근로자에게 부여되는 점심시간 1시간이 법정 휴게시간에 해당한다.

[서울=뉴스핌] 윤창빈 기자 = 박홍배 더불어민주당 의원이 지난해 10월 15일 오전 서울 여의도 국회에서 열린 기후에너지환경노동위원회의 고용노동부 국정감사에서 스마트 안전고리 시연을 하고 있다. 2025.10.15 pangbin@newspim.com

문제는 4시간 근로한 근로자가 퇴근을 희망해도 휴게시간 30분을 채우기 위해 사업장에 더 머물러 있어야 하는 어려움이 현장에서 이어지고 있다는 점이다. 시간 단위 연차 사용에 대한 명확한 법적 근거가 없어 사업장별 운영 기준이 상이하고, 육아·돌봄·자기계발 등 다양한 생활 수요에 현행 제도가 대응하지 못한다는 지적도 제기됐다.

개정안의 골자는 근로자가 4시간 근무 후 바로 퇴근할 것을 명시적으로 요청한 경우, 30분 휴게시간 없이 퇴근할 수 있도록 근로시간 유연성을 높인다는 것이다. 연차는 근로자의 의지에 따라 시간 단위 등으로 분할 사용할 수 있도록 보장하는 내용도 담고 있다.

반차 법제화 및 반일 근무 시 휴게시간 미적용 명문화는 지난해 12월 실노동시간 단축 로드맵 추진단의 논의 결과에도 포함됐다. 당시 추진단은 반차 사용의 경우 올해 법제화할 것을 목표로 제시한 바 있다.

박홍배 의원은 "반일 근무가 늘어나는 현실에서 4시간 근무 후 바로 퇴근하려는 노동자에게 휴게시간 때문에 추가로 사업장에 머물도록 하는 것은 제도와 현장의 괴리를 보여주는 사례"라며 "근로시간 제도도 변화하는 노동 현실에 맞게 합리적으로 정비할 필요가 있다"고 강조했다.

sheep@newspim.com

2026-03-12 10:07

사진

사진

삼성 '갤럭시 S26' 글로벌 출시

[서울=뉴스핌] 서영욱 기자 = 삼성전자가 3세대 인공지능(AI) 스마트폰 '갤럭시 S26 시리즈'를 글로벌 시장에 출시하며 프리미엄 스마트폰 경쟁에 속도를 낸다.

삼성전자는 '갤럭시 S26 시리즈'와 무선 이어폰 '갤럭시 버즈4 시리즈'를 11일부터 세계 주요 국가에서 판매한다고 밝혔다. 한국·미국·영국·인도 등을 시작으로 약 120개국에 순차 출시한다.

미국·영국·인도·베트남 등에서 진행된 갤럭시 S26 시리즈 글로벌 사전판매는 주요 시장에서 전작 대비 두 자릿수 증가를 기록했다.

'갤럭시 S26 시리즈'를 체험하는 유럽,동남아 소비자들 [사진=삼성전자]

◆프라이버시 디스플레이 탑재…카메라 기능도 업그레이드갤럭시 S26 시리즈는 하드웨어 성능을 높이고 갤럭시 AI 기능을 강화했다. 카메라 경험도 한층 개선했다.

최상위 모델 '갤럭시 S26 울트라'에는 '프라이버시 디스플레이'가 처음 적용됐다. 측면에서 화면 내용을 확인하기 어렵게 설계한 기능이다. 스마트폰 사생활 보호 기능을 강화했다.

AI 기반 통화 기능도 추가했다. 모르는 번호로 걸려온 전화를 AI가 대신 받고 발신자 정보와 통화 내용을 요약한다. '통화 스크리닝(Call Screening)' 기능이다.

카메라 기능도 대폭 개선했다. 저조도 촬영 '나이토그래피', 영상 흔들림을 줄이는 '슈퍼 스테디', 텍스트 입력 기반 편집 기능 '포토 어시스트'를 지원한다. 이미지·스케치·텍스트 입력으로 창작물을 만드는 '크리에이티브 스튜디오'도 포함했다.

삼성전자는 3월 구매 고객 대상 프로모션도 진행한다. 갤럭시 버즈4 10% 할인 쿠폰과 정품 케이스·액세서리 30% 할인 쿠폰을 제공한다. 60W 충전기 할인 쿠폰도 지급한다. 콘텐츠 혜택으로 '윌라' 3개월 구독권과 갤럭시 스토어 게임 테마 8종도 제공한다.

마그넷 기반 신규 액세서리도 선보인다. 마그넷 무선 충전기와 카드 월렛, 링홀더, 미러 그립 스탠드 등이다. 마그넷 무선 충전 배터리팩은 스마트폰 후면 부착 시 카메라 간섭 없이 충전할 수 있다.

삼성전자 모델이 '갤럭시 S26 시리즈'의 '수평 고정 슈퍼 스테디' 기능을 체험하는 모습 [사진=삼성전자]

◆하이파이 사운드 '버즈4' 출시…AI 기능·케이스 라인업 확대삼성전자는 무선 이어폰 '갤럭시 버즈4 시리즈'도 함께 출시했다. '버즈4 프로'와 '버즈4' 두 모델이다. 하이파이 사운드와 인체공학 설계를 적용했다.

'헤드 제스처' 기능도 새로 넣었다. 사용자가 고개를 움직여 전화 수신과 빅스비 제어를 할 수 있다. 다른 갤럭시 기기와 연결하면 AI 음성 호출과 실시간 통역 기능도 활용할 수 있다.

버즈4 시리즈는 화이트와 블랙 두 색상으로 출시된다. 버즈4 프로는 삼성닷컴과 삼성 강남에서 핑크 골드 색상도 판매한다. 사전 구매 고객 약 90%는 버즈4 프로를 선택했다.케이스 제품도 확대했다. 전통 문양·통조림·레트로 게임기 디자인 케이스를 출시한다. 헬리녹스 러기드, 초코송이 협업 제품도 선보인다.

전통 문양 시리즈는 꽃과 호랑이 문양을 자개 디자인으로 구현했다. 버즈4 케이스 중 판매 비중이 가장 높았다.

'갤럭시 S26 시리즈'를 체험하는 유럽,동남아 소비자들 [사진=삼성전자]

정호진 삼성전자 한국총괄 부사장은 "'갤럭시 S26 시리즈'는 AI폰을 안심하고 사용할 수 있는 기능부터 갤럭시 AI, 카메라까지 완성도를 크게 끌어올린 제품"이라며 "풍성한 사운드의 '갤럭시 버즈4 시리즈'와 함께 갤럭시 생태계를 경험해 보길 바란다"고 말했다.

syu@newspim.com

2026-03-11 08:49